The Great Mustard Crisis of 2022

.The great Mustard Shortage of 2022...What has happened to all the mustard, our friends ask?...the battle cry of a duke...Normandy's tradition springs back to life

Chères amies, chers amis,

And forthwith…

“Ça me monte au nez!” exclaimed Pierre.

“That burns my nose!”

The French expression expresses outrage, indignation, even fury. Pierre’s black eyes sparkled dangerously and his nostrils flared.

Our neighbor, tall, black-haired, robust, is the picture of a crusader knight. If he weren’t so hale and lively, it would be easy to imagine him carved in stone and lying atop a stone casket in some ancient Norman church, clothed in mail, eyes closed, slight smile of small, full lips, long, prominent nose, arms piously crossed on his breast, and a huge sword by his side.

The constraints of modern life pinch his active temperament like a suit that is too small.

“La Macronie! They don’t want us to enjoy anything anymore.”

Our other neighbor sniffed. She had just mentioned that the government was about to enforce a new law that will put a stop to “la fast fashion” – cheap clothes made to be discarded and thrown away.

“A good thing, too,” she stated.

In the 25 years since we have been friends, Ranehault has worn one particular style of dress, adapted to activities as varied as berry-picking with our children to a fancy winter wedding. It is a mid-length, high-waisted frock that she sews herself out of fabrics that might as easily come from a salvaged swathe of antique damask velvet found in grandmother’s armoire as a bolt of fine Liberty cotton.

The law, she informed us, includes many directives, aimed also at fast food and other wasteful, unhealthy habits.

“Are the poor to have no vices?” remarked Monsieur, with a mischievous gleam in his eye.

“No cheap clothes, no cheap cigarettes, no cheap gas?”

“And no mustard!” added Pierre in a scandalized tone.

For mustard has vanished from the shelves of France’s grocery stores.

Mustard is the third most consumed condiment, after salt and pepper, in France. The average Frenchman – and there are 65 million of them in the hexagone -- eats 2 pounds of mustard a year. It is taken with ham, the most widely consumed meat in the country. You mix it with crème fraîche and ladle it over rabbit for lapin à la moutarde. No proper vinaigrette is made without a dash of mustard. And mustard is such standard fare that “le verre à moutarde” is a commonly used measurement in cooking.

On our way back from Paris, Monsieur and I had stopped in at the boucherie-charcuterie of neighboring Sainte-Scolasse-sur-Sarthe to buy provisions. Le boucher exchanged pleasantries with his first customers as he wrapped up their order in waxy white paper, and we inspected the glass cases of meat and poultry, terrines and pâté, cold salads and prepared dishes to take home.

Home from the charcutier…without mustard

Le charcutier is an ancient corps de métier. The guild once sold only cooked and prepared pork, but in 1513 les charcutiers wrangled the right to sell fresh pork as well. As a butcher and a charcutier, Monsieur Grapain sells just about anything connected to fresh and prepared meat, including bottled vegetables and condiments to serve with it.

During the pandémie, when grocery stores and restaurants closed and Parisians fled to the countryside, Boucherie-Charcuterie Grapain cheerfully enlarged its offer. So along with two pork grillades and several diaphanous slices of jambon du pays, we filled our basket with beurre d’Isigny, half a hand-made sheep’s cheese, local honey, olive oil, a bag of locally milled flour and a fancy kind of tiny black lentil called “beluga” after the caviar it resembles.

A hand-written sign propped up on the counter declared, “Moutarde en vente en vrac.” Mustard for sale in bulk!

“Bulk mustard?” I asked, astonished.

“Oui, 7 euro le pot!” he replied.

“When you bring the pot,” he added, with a rather sheepish grin.

“Seven euros!” cried the other clients. A large pot of cheap mustard in a supermarket used to cost less than a euro.

“But,” continued Monsieur Grapain, “I don’t have any left.”

He tilted the plastic bucket of mustard so that we could see it had been scraped clean.

A silence fell. The following day was Jeudi de l’Ascension, a national holiday celebrating the heavenward ascension of Jesus after the Resurrection. There would be no deliveries of mustard or any other commodity on the Feast Day.

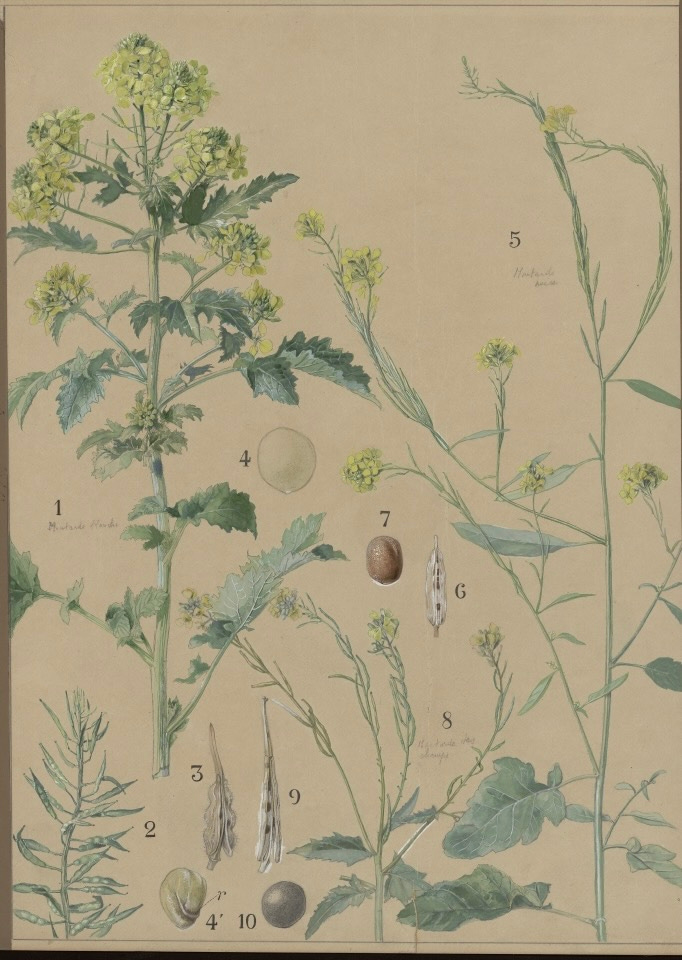

An early 20th-century sheet shows the parts of the black and white mustard plants.

There are several popular explanations for the “crise moutarde” that is emptying France’s grocery store stocks of mustard: war, climate change, a government initiative to deprive les citoyens of life’s pleasures, also known as “le grand reset” and exemplified by the loi anti-fast fashion, and hoarders. These later are so fearful of a mustard shortage that they buy up all available stock, thus depriving others.

“And then perhaps they will try to sell them on the black market,” suggested Côme, darkly. The 22-year-old son of friends from Paris, he was passing through Courtomer and had joined us for l’apératif.

It is true that the last time France knew a mustard shortage was during the Occupation, when food was rationed, all food imports stopped, and a black market flourished.

“It’s the drought in Canada and the war in Ukraine,” stated Ranehault, authoritatively. “People will just have to get used to it. We’ve all got to tighten our belts.”

Pierre’s eyebrows shot up. He is a farmer.

“Si tu me permets, ma cousine, it’s the new law restricting insecticides on mustard plantations,” he corrected. “How does one expect our mustard-seed growers to compete with foreigners? Why even in that mustard seed they discovered – voyez, from the Third century, in that amphora in Poitiers – they found insects of the Third century.”

He looked over at his cousin with belligerent satisfaction.

“And le mondialisation!” put in Côme. “Agro-industrie!”

Pierre and Ranehault ignored Côme’s interjection. Yes, they concurred, who could afford to make anything in France, with foreign competition so cheap? Pierre himself thought that French wages and les charges sociales – labor taxes -- were out of control, while Ranehault and Côme thought that wages and benefits around the world should rise to French levels.

Monsieur cleared his throat. He is an economist – a moral philosopher, as he likes to say.

It is true, he proffered, that a drought has cut Canadian mustard seed production by half. And mustard seed is no longer coming from Russia and the Ukraine these days.

It is true that in the three years since new insecticide restrictions have been put in place in France, the production of mustard seed has fallen by two-thirds.

On the other hand, the seed which “indeed is the least of all seeds, but when it is grown, is the greatest among herbs,” as the Bible parable so rightly puts it, grows all over the world. And ever since mustard production was industrialized, French mustard-makers have used imported seed to meet demand. Nepal, an alternate supplier, produces as much mustard seed as Canada.

“It’s the pandémie!” exclaimed Pierre, returning to the charge. “Inflation!”

“Perhaps you mean policies put in place during the pandemic,” continued Monsieur, looking over his glasses with professorial severity. “Production and transportation stoppages. Printed money to compensate for lost revenue and wages. These are causes of inflation.”

“True,” said Ranehault thoughtfully. As a concerned citoyenne and a cook passionnée, she had been reading up on mustard.

Already in 2021, she told us, the director of France’s last family-owned moutardier had sounded the alarm: French mustard was “en peril.”

In an article in “France 24” last December, the grandson of Edmond Fallot, founder of the venerable Moutarderie Fallot in 1840, had listed the sector’s woes: in addition to mustard seed scarcity and its rising cost, metal caps were up 42%, glass jars up 12%, cardboard for boxing up 12%, and white Burgundy wine, a vital ingredient for Dijon mustard, up 50%. Plus, Fallot exports half its mustard to Japan and other parts outremer. And the cost of maritime freight was up as much as 600%.

We looked rather gloomily at our apéro, featuring jambon du pays on thick slices of fresh bread spread with Normandy butter. Should we hide our remaining pots of mustard?

The use of “la graine de Sénevé” or seeds of Sinapis, the mustard plant, as a condiment came to France with the Roman conquest of 52 B.C. The Romans called the fermented mustard seed concoction “mustum ardens” – “burning must” or moût ardent -- hence the French word “moutarde.” Mustard in France is still made with the white mustard (Sinapis alba), favored by the Romans, as well as the more pungent S. nigra, black mustard, mixed with wine or cider, vinegar or “moût.” Moût, or must, is juice made from crushed fruit, high in sugars that also ferment into wine, cider or vinegar.

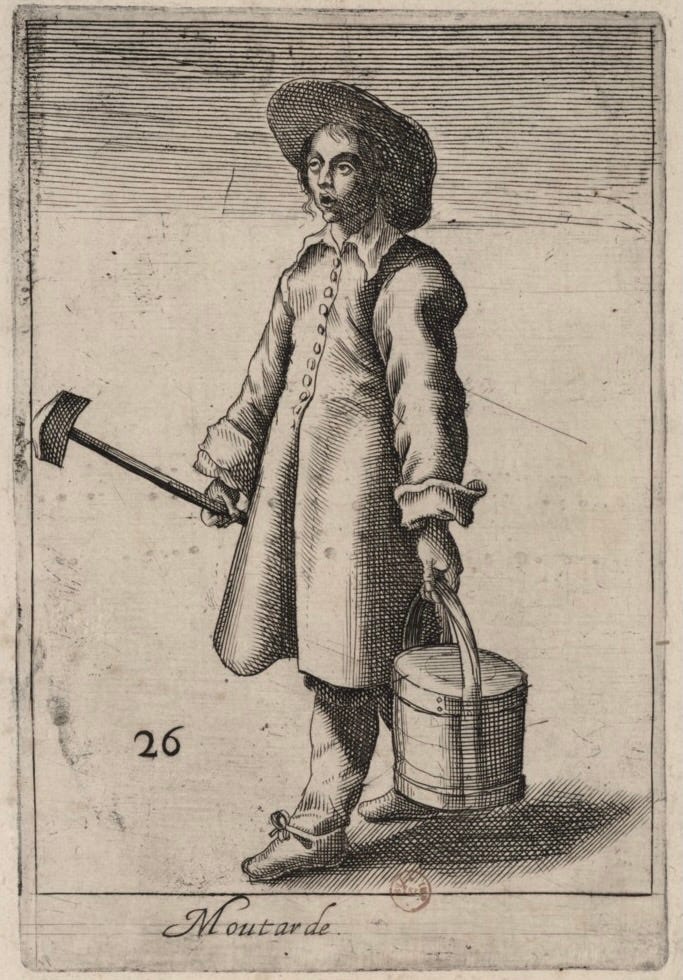

A 17th-century mustard seller, from a French engraving at the BNF.

From the start, the French took to mustard. In the Middle Ages, the mere métier or trade of moutardier was elevated into a full-fledged corporation, joined to that of the vinegar-makers. Les moutardiers et vinaigriers had the exclusive right to make and sell mustard. As a “métier juré,” the guild swore to the quality of ingredients and the cleanliness of its mustard mills. By the time this honor was awarded in 1394, French mustard from Dijon was already being exported throughout Europe as a delicacy.

“The Dijonnais even claimed to have invented the word moutarde,” added Ranehault, disapprovingly. According to Burgundian lore, the word derives from the banner flown by the victorious troops of Philippe le Hardi, Duke of Burgundy, whose capital city was Dijon.

“After the Duke’s military campaign in Flanders, Dijon’s devise became “Moult me tarde!”,” she continued. “This was Philip the Bold’s battle cry. In Old French, it means “everyone waits for me,” because the arrival of the Duke and his troops would turn the fortunes of war.”

Following the lucrative sack of Courtrai in 1382, the final siege of the campaign, Philippe had the motto sewn onto his banner.

The citizens of Dijon, anxiously awaiting the returning soldiers, dimly perceived the distant ducal flag as it fluttered in the wind. They saw only the words “Moult…tarde.”

“Moutarde, moutarde!” they cried.

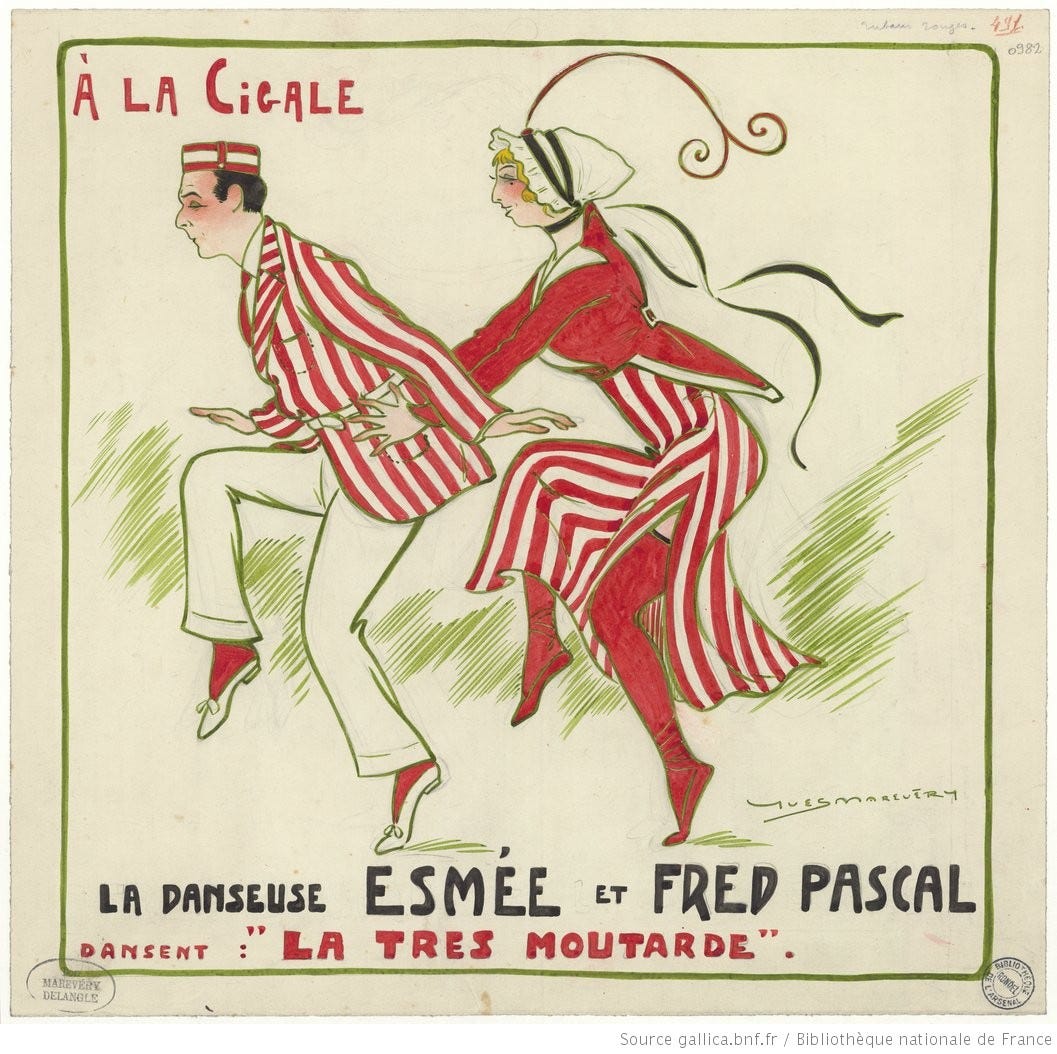

“Très moutarde!” interjected Pierre, chuckling. This, it seems, is the title of a turkey trot danced by his grandparents in their younger days. He and his sisters used to listen to it on the family’s ancient victrola.

“Too Much Mustard” goes the title of the jaunty hit tune in English. There is a bit more to know about mustard, however.

Dijon has been practically synonymous with French mustard since those early days. Nevertheless, the condiment was made in all the wine- and cider-producing regions of France.

Normandy’s mustard was traditionally made with moût from apples and from the cider and cider vinegar for which the region is famous. In our neck of the woods, it was also made with a pinot grape varietal known locally as Verjutier de Sarthe. This pineau gris was grown not for wine, but to produce verjus. Literally “green juice,” verjus is made from pressing unripe grapes. From antiquity until the beginning of modern times, verjus was widely used in cooking and as a cure for indigestion.

“On faisait des barriques entières de verjus chez les seigneurs et dans les couvents,” writes an historian. “One made quantities of verjus in chateaux and in monasteries.”

Ordinary people bought their verjus from the “ moutardiers et vinaigriers.”

The privations of World War II, as noted above, put a complete stop to mustard production in France. After the war, newly introduced farming techniques and subsidies made mustard seed less profitable than other crops. And changes in production and consumption in post-war France – like the advent of la grande distribution, ITnational grocery chains -- squeezed out the kind of small family firms that had manufactured the hundreds of regional mustards.

Normandy’s last and most famous mustard maker, Maison Bosquet founded in 1735 in Yvetot, closed shop in 1992.

But, as suggested by the motto of the victorious duke, everyone wants mustard. Founded in 2020, the year of the pandémie, Maison Dupont is a one-man moutarderie working with mustard seeds from a local farmer and apples from local farms. Robert Dupont is based in Martin-Eglise near Dieppe.

Perhaps a visit to Dieppe is in order, we suggested to our friends, as l’heure de l’apératif came to a close and we exchanged our adieux.

“Moult me tarde!” agreed Pierre.

A musical score for "La Très Moutarde." Written in 1911 as "Too Much Mustard," it was translated into French and a highly popular dance tune on both sides of the Channel through the 1920s.

A bientôt au Chateau,

Elisabeth

P.S. To turkey trot to La Tres Moutarde...

P.P.S. And pour le fun:

An 18th-century recipe for Mustard

According to Diderot’s authoritative "Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers" of 1751, this is how mustard is made:

Soak mustard seeds in vinegar for 24 hours, then press liquid out and pour off. Reserve liquid.

Use the reserved liquid to macerate chopped parsley, chives, garlic, celery or other herbs for 15 days.

Grind the seeds with moût, verjus, wine, or cider. Then, if you wish, add quatre-épices (white pepper, ginger, nutmeg, and cloves), dried thyme, cinnamon, and tarragon.

Add olive oil to the mustard mix, then the vinegar used for maceration.

Wait 2 days, add salt. If kept in a bucket, a thin skin of olive oil ladled over the mustard preserves it from air. Otherwise, put into pots, cork, and seal with wax.

**

As always, Heather and Beatrice (info@chateaudecourtomer.com and +33 (0) 6 49 12 87 98) will be happy to help you reserve your holiday or special gathering at the Farmhouse or the Chateau. We still have a few openings for this year and are taking bookings through 2024. Please feel free to call or write us.

Yvetot and Dieppe are in Seine Maritime, not Calvados